The first 100 days

Author

Tom Scott

I speak to those who move from Senior IC into leadership and realise the difference when adapting, and how leadership can be lonely. I talk about the first 100 days in a role because, in my experience, it’s the leading indicator that a leader will work out long-term.

I sat down with Andy Polaine a design leadership coach, educator, writer and co-author of the Rosenfeld Media book, Service Design: From Insight to Implementation, now a standard text for Service Design.

He can be found at polaine.com, writes a newsletter called Doctor's Note and hosts the Power of Ten podcast. He is currently in the early stages of writing a new book about the psychological experience of moving into design leadership.

The first 100 days as a Design Leader

1 - How do you see the state of design leadership today?

Design is in a curious place at the moment. After a couple of decades of pushing upwards to be more strategic and connected and having some success at higher levels of organisations, design functions have been split up again in many orgs.

Design leaders were previously able to build up a coherent practice in the organisation, combining design research, service design, strategic design, UX and visual design and more. These often worked as a kind of internal agency, constellating and re-constellating teams as projects flowed through. The advantage of this approach is an increased maturity and culture of quality that can be built up over time, plus much more sharing of ways of working and systems that maintain consistency across all touchpoints. There’s a reason our book’s tagline was “from insight to implementation.” That red thread and traceability are essential to maintain, even while teams work on different parts of a product or service (and most of them are services).

For design leaders, their job was to manage that culture, quality and growth, collaborate and make the case for design’s impact at higher levels in the org. The rapid rise of product management has added another layer of stakeholders to interact with and the product leaders have a loud voice at present. When it goes well, it can be an excellent collaboration between business needs, design and engineering. But in many orgs it has re-industrialised design, by which I mean feature factories. The white-collar management in the glass box do all the thinking and the blue-collar workers merely execute on the assembly line. Design teams split across feature or moment-in-the-journey teams are disconnected and usually a minority voice in that team, most often run by a product manager. This is a challenge for design leaders, who are trying to maintain quality and coherency across the discipline, but are having to wrangle with the silos once again.

I would argue that product is far less mature than design as a discipline—it’s simply not been around as long—but design has, as ever, done a terrible job of communicating the impact of design to the org and has suffered as a result. The Achilles Heel of design leaders is that they talk about design too much. It does feel like design leaders have to repeat the past 20 years all over again.

2 - What are the main concerns/challenges new design leaders face? How do they overcome these from your experience working with hundreds of new leaders?

The biggest one is confidence. It can be very discombobulating to unravel an identity woven from many years of experience of being someone who makes things. There’s much more to say about this, but the short version is that this identity is often forged quite young – at college or even at school where many designers leaned into their “talent for creativity or drawing” having been told they weren’t very “academic.” Fast forward 20 years and the same dynamic is often at play at work. Design leaders are frequently the only designer at their level in a much larger org.

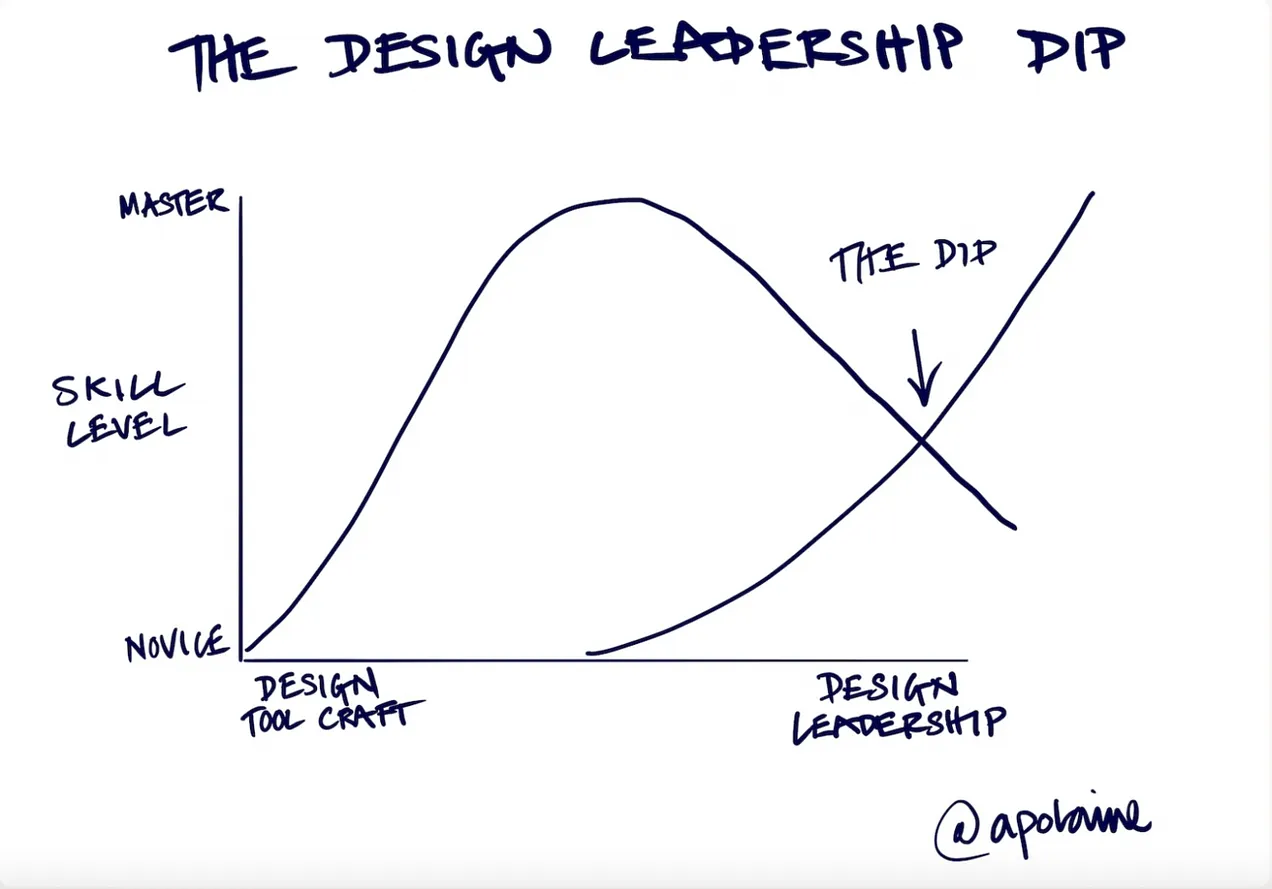

As designers start to let go of some of their “on the tools” craft skills and take on more business, people management and leadership responsibilities they can go through what I call the Design Leadership Dip, where their confidence is rattled in both craft and leadership. Imposter syndrome can quickly set in.

Unless you are lucky enough to have had a role model or mentor, you’re faced with making things up as you go along and this can feel terrifying, since you’re always waiting for the moment you’re going to be found out. But the dirty secret is everyone else is making it up as they go along—that comes with the job of being out front leading. It takes some time to remember that you are one of, if not the, most experienced design person in the org and that’s why you’re in the leadership role.

Design leaders need two different vocabularies. One is talking design to designers, the other talking impact to the org’s stakeholders. If you’ve spent 10-20 years talking about human-centred design, design process, and design minutiae, it can be a difficult habit to break. It can come as quite a shock to realise senior leadership doesn’t really care about design at all. They have different metrics they are focused on and design leaders need to learn to link those to whatever they’re also trying to achieve for the org.

That does not mean jettisoning everything design and becoming a numbers person. You will lose the special lens you bring to conversations with senior leadership. If you do that, what’s the difference between you and any other MBA apart from your slide decks looking way better? But design leaders do need to re-think the storytelling of how they talk about design.

3 - What advice would you give non-design executives who hire design leaders on when is the right time to bring in a design leader?

Tom: I believe one of the main reasons why design leaders are leaving rapidly is due to being brought into the organisation at the wrong time and not having meaningful OKRs that link back to what the C-Suite cares about. What do you think?

As early as possible. I know it’s a common question, but it’s also odd when you think about it. We don’t often hear senior execs ask when the best time to bring in management or engineering is. This is a sign that design still hasn’t done the best job of explaining to business folks how it can best be leveraged and the impact it can make. But it’s also a sign that organisations are not doing the necessary structural work.

The reason for bringing in a design leader from the start is that it helps infuse the organisational DNA with different ways of working and collaboration between and across functions from the start. Primarily, though, organisations need to avoid racking up design and experience debt in just the same way they need to manage organisational and engineering debt. Without this, it makes them extremely vulnerable to disruption from a competitor. Tech is often easy to copy. Experience is much harder to copy.

So, yes, setting up those metrics that are directly aligned with what the organisation is trying to achieve is essential. For that to happen, the C-Suite needs to have an ambition, purpose and strategic vision that can filter down and draw up. This is surprisingly rare.

4 - How do you navigate your first 100 days in a new design leadership role?

Do your discovery. Find out what other stakeholders in other functions do, and what their needs, fears and anxieties are. Do lots of listening and then work out what needs to be done, for sure, but think more in terms of how design can help those stakeholders and the business with those problems. That way you’re operating on a pull rather than push basis.

Before hiring for a bunch of roles that you think make sense in terms of a design org chart, think instead about what the design jobs to be done are. Cluster those jobs and think about what kinds of people might be able to do them. People have many more skills than their job title and it opens up the opportunity to hire some different flavours of creative folks. If you’re just starting, you can also think about who you might hire who can cover multiple jobs to be done.

Hopefully, readers can see the relationship between those two approaches – it’s very much a human-centred design approach to the problem space.

5 - What is the difference between a good leader and a GREAT design leader? How can someone become a great design leader?

Well, first I’d question the premise of this question a little. Much as with parenting, you’re doing well if you’re doing good enough. Banal as it sounds, I’d say a great leader helps people thrive and is equal parts inspiring and encouraging so their teams aim high, but not at the expense of burning out. It’s so easy to get swept up in the management race to chase made-up numbers and growth for growth’s sake. Leaders who say things on their LinkedIn profiles like “I drive results” usually slave-drive their teams.

The thing that makes someone great as a leader is authenticity. They don’t try and be what they’re not. They don’t try and pretend they know all the answers. They usually have a real connection to people. “Authentic leadership” has become a bit of a trite term, but underlying it is a really hard question that takes a lifetime to answer: “Authentic to what?” In a leadership role, all the personal complexes and issues you have are magnified, so you need to do your inner work, understand where you come from, what you are about, your values, your complexes and issues in order to become friends with yourself, warts and all. Once you have nothing to prove, you have less reason to act in ways that are not in line with your sense of self. If you don’t know the interactions and issues that turn you into a monster, you’ll be a terrible boss. We’ve all been on the other end of one of those.